Is there more to life than this?

The making, and unmaking, and remaking of this writer

I was eight. I was at a friend’s house. They had a big family, and it was Christmas time, and it was noisy. Amid the chaos, I found a typewriter. I sat there and picked out some words. I loved how clattering on the keys made my thoughts appear on paper.

A few days later I wrote down a whole story. I liked that whole experience very much. I kept on writing through school. Homework, fragments of poetry, song lyrics.

It was interesting, but frustrating. I knew there were jewels here, glowing in the dark, but I couldn’t grasp them …

I was nineteen.

Pine trees, sand dunes, heat. I was sweltering in a tent near the beach at Soulac-sur-Mer in South West France. I'd hitchhiked down there at the end of June, and been there for weeks, swimming, hanging out with the campsite workers, enjoying the sense of nothing to do and a big wide world before my first year at university.

The evening before I'd heard three people had died swimming off that same coast that same summer. I loved the beach, being out in the world for the first time, and I especially loved swimming in the sea. That three people had drowned nearby at practically the same time seemed bizarre. Eerie even.

Out of nowhere I tried to write down what I felt. A strange image came to mind: a man walking across a field of maize. The maize was high, and blotted out the horizon as it waved in the wind. The man seemed to be walking in a bubble, alone, against a big sky. I couldn't make sense of it all, or what I was trying to do.

I stopped writing, went for a swim, forgot about it all.

*

My mother bought our family a strange present for Christmas. A personal computer. No-one knew what it was, or what it was for.

After experimenting, I realised this strange device made writing stories seem like playing video games. I liked video games so I took out the notebook I'd kept from Soulac, and lots more scraps of writing I'd made.

Three days later I finished my first short story, and the man in the cornfield was in there. I called it Indian Summer and I sent it off to a competition that the publisher Victor Gollancz was running in conjunction with the Sunday Times.

It was shortlisted, and was eventually published in the book of the competition. That lit the fire alright.

*

Some years later, I sat in a lecture theatre in London, desperately trying to write down every word the irascible man on stage was barking at the audience.

Ever since the Amstrad I'd written a ton of short stories. I’d even sold another one of them. I'd begun, and abandoned, three novels. That wasn’t enough for an entire decade.

I'd spent an awful amount of time, and money, and life, on writing fiction, but I was clearly missing something crucial.

As a desperate last fling I turned one of the short stories into a screenplay. A friend who was working in the BBC Drama department read the script and liked it enough to called me in for interview. I ended up with a six-month contract as a script reader.

The first thing the BBC Drama Dept did was send you on the Robert McKee Story course. Where he shouted at you. For three whole days. But McKee showed me there was such a thing as story structure, and explained how it might be achieved, and thus closed the gap that had been sparking fitfully for the last 13 years.

Suddenly I understood how I could transform clouds of emotions and thoughts into meaning.

*

A few years later I was hiding in my office in a warehouse called Bosun House in South London. This was the headquarters of The Bill where I had a job as a script editor. I also had a big problem.

A script I had been editing hadn't made the grade. I had picked the wrong writer, and although the cameras had to turn over in less than a week, all I had to offer the director was a pile of parts. This was a terrible situation - there was no way on earth they could not shoot, the system was far too inflexible. I was far too experienced a script editor by then to have let this happen. But luckily the situation was too far gone: the only thing left was to make it work.

For the next two days I sat with the director, the series script editor, and the supercharged ace in the hole, a wonderful man called Michael Simpson. He was the producer on the episode, was unfailingly kind and courteous, and had thirty years of experience of television drama.

Between us we batted that story round and round, up and down, never writing down more than the odd note.

At the end of those two days we had our story. The series editor and I scribbled down a bullet point summary, took half each and started writing scenes and dialogue. Two days later we had a script, and it worked, and after one more polish it got filmed and made a great episode. That producer taught me something priceless – a story doesn't live on paper, it lives best in the air between people.

I had been a writer for years, but that experience made me a professional.

A year later I went freelance and started selling my own scripts and stories, to the BBC, ITV, and independent TV and theatre companies. For many years all I thought about was how to write drama. More specifically, how to write drama for money. I did OK, for a long time.

*

After a while I realised something was wrong. Something was eating away at me. The more success I had, the less I valued it.

The first sign was when I worked on a sci-fi show with characters I had loved since I was a child. I was so excited to be commissioned, but that wore off as I worked on it, so badly that I watched it go out, and felt nothing.

Then I got approached by one of the most famous dramatists in England to try out for his show. I actually turned him down. All I could think about was how the development battle I’d have to go through simply wasn’t worth the end result.

A couple of years later I worked on one of the biggest crime shows in Britain. Again, getting hired was such a thrill, and again that wore off fast. To this date, I’ve never watched all those episodes all the way through.

Jim Carrey once said “I think everybody should get rich and famous and everything they ever dreamed of so they can see that that’s not the answer.”

I wasn’t rich, and I wasn’t famous, but I’d worked so hard for thirty years to make it, and I’d finally hit the top of one of the very biggest trees in my bit of the forest.

I’d achieved all I’d dreamed about, and it all felt meaningless.

I thought when I got to that point, I’d finally feel whole, complete, like I’d ‘made it’.

I didn’t feel anything of the sort.

The hole inside me was, if anything, bigger than ever.

I realised that, whatever I had been driving me on was not be found in being a screenwriter.

My quest had failed, right at the top.

That was quite a shock.

*

I still loved writing, and telling stories, but I saw no point in doing that for myself any more.

However, helping people tell their stories through a craft I still loved felt amazing. For a while I worked as a script editor for the BBC, and then I began to teach other writers.

I loved both jobs for a while, but they still weren’t enough. I was, if I’m honest, getting more and more lost. Making worse and worse choices in my life.

Some years passed like this, with me growing a business and looking like I was doing just fine, while actually, away from that, I things were going from bad to worse.

*

Until in 2017 a greater power called me, and I became a Christian.

A friend heard my latest mad scheme to improve my life, and suggested that, instead, I take an Alpha course.

With great reluctance I went along to my local church. And slowly I heard how there really was truth, and meaning, and purpose.

Apparently, it was all to be found in the Gospel, and in the person of Jesus Christ, who had died to set me free from my sins.

It was the strangest message I’d ever heard, and at first I thought it was nonsense.

But it wouldn’t leave me alone. Slowly I began to feel that the whole Christian thing was pure, and beautiful, and honest, and timeless.

Was this what I’d been looking for?

I can still remember standing in the basement of a hotel in Eastbourne and saying to myself ‘OK, Jesus, go on then. Let’s see if you’re real. I’ll trust you for a bit and see how that works out.’

That’s when my world exploded. Over the next few weeks my already wobbling value system finally tumbled down completely.

Everything I thought I knew about how to live fell away, every idea of worldly success evaporated, to be slowly replaced by a confusing message of surrender, and a much greater purpose.

‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind … Love your neighbour as yourself.’

After all my years in the very venal TV industry that idea took some adjusting to, believe me. But it hounded me and wouldn’t let me go, and I realised I’d have to change.

*

I did change. Slowly, at first and then quickly, almost overnight in fact, at a huge church festival in Dorset.

The music was Christian worship music, and the musicians included Elle Limebear, Martin Smith and Bright City.

Being in that crowd is the most extreme example of the fusion between band, audience, and God I’ve ever experienced. A tent full of 7,000 people came together, some with their hands in the air, some on their knees, all praising Jesus as one. Unforgettable, and life changing.

It was on that holiday that I promised to direct as much of my writing talent as I could towards building God’s kingdom.

I had realised something very vital. That, for me, this was the way to find genuine fulfilment.

In the course of that holiday I guessed that, if I could write my own stories and help other people tell theirs, and each story reflected, in some way, the glory of God, then that was something that could never feel hollow and empty.

And, do you know what, I was right. Writing from this place is my ultimate purpose.

These days I only write about things that I love, because I love them, and I want to tell other people about that love.

My goal is to write because I feel the light of love, and to help others experience that light.

All that was left was to find the platform.

*

I’ve written elsewhere about the precise moment I fell in love with the police.

That was a moment deeply embedded in the ordinary world. At that moment I saw heroism that could only come from sacrificial love.

Reconsidering that memory crystallised everything for me, and I recognised that I had found the right arena.

Crime books are a perfect vehicle. They can reach a wide audience, there are endless stories and they can explore what I love. They combine strong commercial viability and they can point towards the light.

That makes them the most exciting thing I can think to be writing as I go into this next phase of my life.

I hope you enjoy my books.

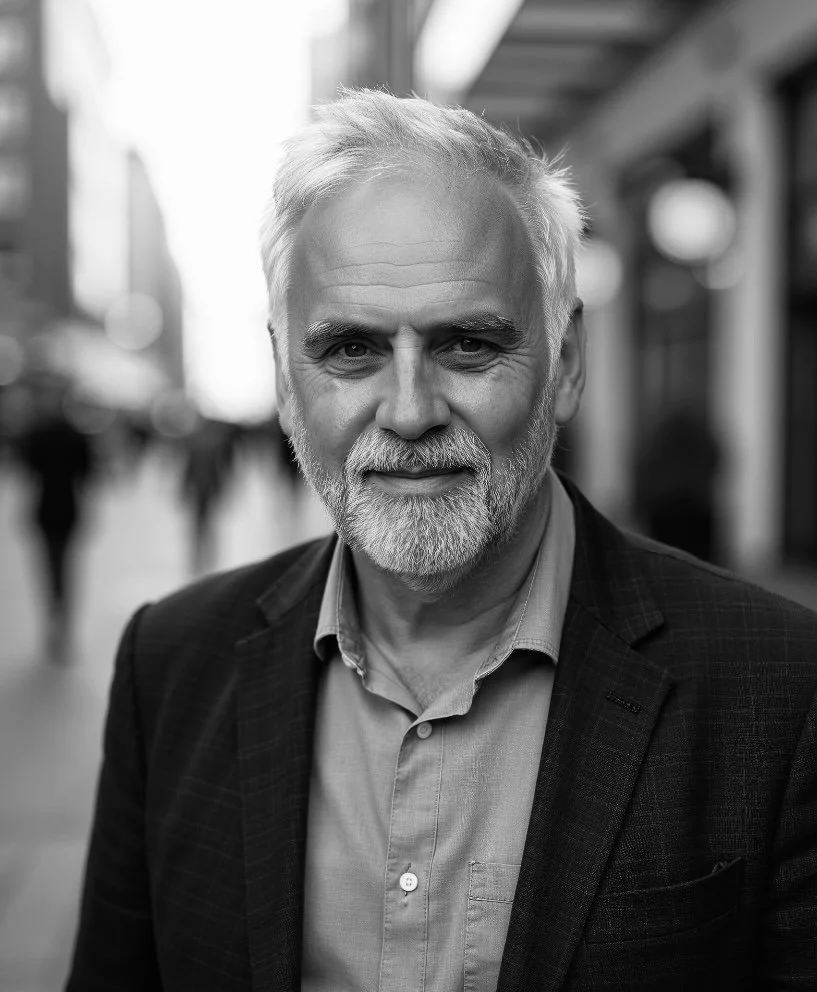

~ Philip