Manifesto: Stories That Run Deeper

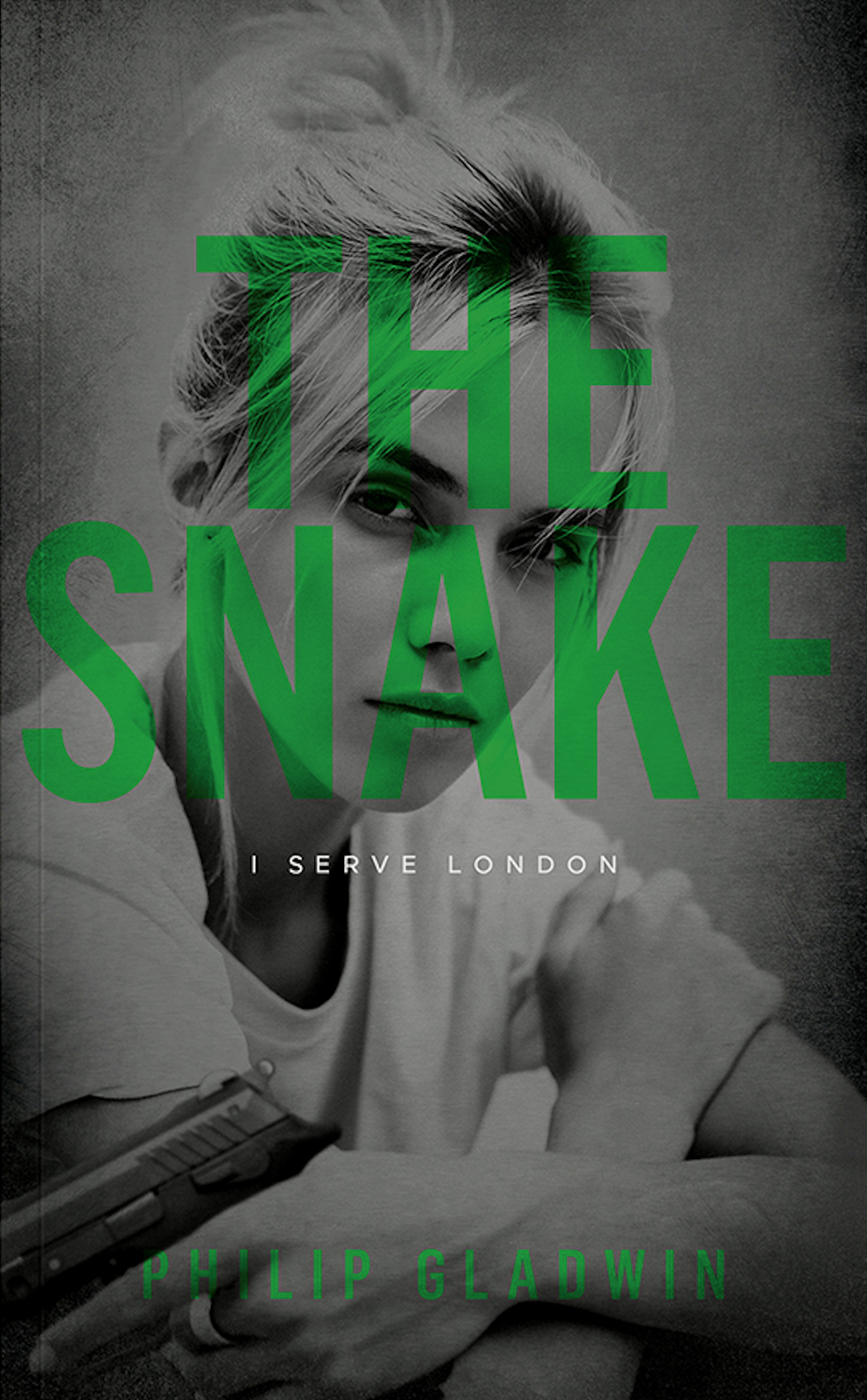

This is the cover of my next novel, The Snake. It’s a thriller, and it is the first novel about the Metropolitan Police's SO19 armed response unit (the early years of the Specialist Firearms Command). It will be released in early Spring 2026 and I’ll speak more about it nearer the day. For now, I want to talk about the cover.

I don’t know who the woman is; I found the photo in a stock photo library. I stopped in my tracks when I saw her, because I recognised the look in her eyes.

Her face says she is determined, resolute, defiant, courageous — and somehow bruised by life.

These are all characteristics of the lead character in The Snake.

You can see this look written on many people, from all walks of life. It shows enormous pain, and enormous depth of character.

The most dramatic time I’ve ever seen this look is in this famous picture of a British airman from the Second World War.

This photograph has haunted me for years.

It was taken in September 1940, at the height of the Battle of Britain and the Blitz on London. The man in the middle facing the camera was called Brian Lane. He was also leading 19 Squadron - Britain’s first squadron of Spitfires.

It had been a wild summer. In May 1940 he flew sorties to provide air cover over the beaches in Dunkirk.

In June he had his 23rd birthday and got married.

In July he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Through August and September he and his small team flew endless defensive sorties above Kent as part of a last-ditch attempt to stop the imminent Nazi invasion. Those few planes of the RAF were the last resort before a full land invasion of England.

Can you imagine the strain by the time this photo was taken in September? He’d had months of broken sleep, and daily battles with a powerful enemy airforce that was determined to kill him.

Look at his face. The tightness of his jaw, his haunted eyes, the lines on his face, the way he grips his cigarette. It all shows what months of defending his country had done to him.

Brian Lane was last seen on 13th December 1942, when he and and three other Spitfires encountered a group of Focke-Wulf 190s near the Dutch coast. He engaged them, and was last seen heading off in pursuit of them. He is believed to have been shot down over the North Sea, to the west of Schouwen Island, but his body was never found.

I find this kind of courage, bravery, and commitment absolutely compelling, and I always respond to it when I see anything like it around me.

I always want to write about it, but it’s hard to find it in most areas of normal life (and I really do want to write about normal, everyday life).

This is my main reason for embarking on a series of novels about the police.

(Now, I know that the police get a VERY bad press at the moment, but hear me out.)

So, why the police?

I’ve actually spent much of my career writing about the police in one way or another. From episodes of The Bill, to battling the intricacies of a troubled Midsomer Murders plot. From writing dark tales about murderers for Lynda La Plante in Trial & Retribution, to script editing and helping storyline the comparative lightness of New Tricks, to developing many other police shows that never saw the light of day.

Like many people, I find the police fascinating.

They’re deeply embedded at the sharp end of normal, every day life.

Then there is such a range of people who choose to be police officers, and there are so many jobs in the police there is such difference in what they all do.

They face great pressures, challenges, and dangers. They have great authority, which they can use, and abuse. They get so much right, and they get some things very wrong.

Most of all, why would anyone want to take on all that pressure in the first place?

“There’s no-one else. When things go bad, we’re it.”

From a personal conversation with a serving firearms officer

First hand experience

Just after I started out as a professional writer, I found myself in the basement of an underground carpark in central London.

I was gathered with three police officers around a black BMW, talking about nothing in particular. It was the last few minutes of normality before I set off for an eight-hour research ride with them.

I’d signed a disclaimer or two. It had been made very clear that whatever happened to me over those eight hours was on my head, and was definitely not the responsibility of the Metropolitan police. There could be absolutely no suing. Or funeral payments.

Funeral payments?

I should mention that all three officers were carrying Glock pistols, and Heckler and Koch carbines, and all four of us were wearing a bullet-proof vests.

I’d done a few similar research trips, riding along with regular police officers as they went around and about, and I’d realise how many amazing, terrible, tragic, and wonderful stories there were out there.

I’d even already already been out to the SO19 training ground but this was the first time I was actually going out on live patrol with the type of officer who carried a gun to challenge other people with guns.

I had been looking forward to the day, and so far I felt safe with them. They seemed capable, and responsible, and were taking good care of me — which included showing off about their equipment.

Before we set off, they taught me how to fit a ceramic plate into the chest part of the bullet-proof vest. This was extra protection against bullets, so was A Very Good Thing.

What wasn’t a good thing was how, when they had fitted the plate and stood back to look at me, they began to laugh.

What? Come on guys..?

They took pity and showed me. I am very tall, and the bullet proof vest was very short on me, so there was a large part of my stomach that was left totally unprotected.

As they pointed out, being shot in the stomach was always terribly painful. ‘Agonising’, one of the officers said, with some relish. But I wasn’t to worry, apparently.

The joking stopped when a call came across their radio. There was an armed robbery taking place at a bank in Southampton Row. The criminals were equipped with firearms, and looked like serious blaggers.

To my great surprise, one of the three officers said words to the effect of:

‘Yeah, we’ll take that.’

All the joking stopped. I caught the sideward glances as they considered me, and the possibilities, and the extra burden the Met Press Office had given them. I’ll give them full credit — they never flinched at the problem I must have presented.

They were very comforting as they explained to me how, firstly nothing would happen. And how, even if something did happen, I’d be nowhere near the action. And, how even if I was near the action, and shots were being exchanged, then all I needed to do was get out the car, and crouch down and take cover …

(And how, to be clear, there was only one place I could crouch down, as bullets would cut straight through a car. I would only be safe once I was firmly behind a small lump of metal like a car engine.)

Once I’d shown I’d grasped all that, and that I wasn’t going to back out, or cause a problem in general, we got in the car, ran the car up the ramp out of the carpark, (slowing marginally to clear the already rising door — a moment of tense waiting) and then we got out into the street, with the car pointing towards Southampton Row.

Almost instantly we found our way blocked by a great gang of teenagers, who clearly had no time for the police, and who deliberately sauntered together in a mob across the road. We were literally on our way to an armed robbery, but we had no choice but to sit still and wait for these hostile teenagers to cross —